Hana Hou: Gigi’s Eden

DEC. 2013 / JAN. 2014 | Original post at Hana Hou

Story by Shannon Wianecki

Photos by Kyle Rothenborg

The Wai‘anae coast is a twenty-mile stretch of startlingly white beaches flanked by tinder-dry mountains. Some of O‘ahu’s prettiest landscape, it’s terrain few tourists see. The small communities strung along the leeward shore—Nanakuli, Lualualei, Ma‘ili, Wai‘anae and Makaha—are proudly Hawaiian. But many families here struggle. Some live in their cars or on the beach. Farrington Highway, the sole way in and out of Wai‘anae, deadends at Ka‘ena Point. In ancient times this windswept outcropping where young albatrosses fledge was known as a leina a ka ‘uhane, a place where spirits leapt into the next world. In modern times it’s a bad place to leave a vehicle unattended.

When Father Luigi “Gigi” Cocquio arrived in Wai‘anae in 1979, he bypassed the parish rectory and instead moved onto a vacant church lot down the road in Makaha. The sun-scorched land was choked with weeds and home to three dilapidated Quonset huts — a place as marginalized as the young Italian priest himself. He’d come to Hawai‘i uninvited, having been expelled from the Philippines. Reluctantly the bishop of Hawai‘i had assigned him to Sacred Heart Parish in Wai‘anae. Perhaps there the black sheep would be too far out to pasture to cause further trouble. As they say, God works in mysterious ways.

With his very first sermon, Father Gigi managed to ostracize half of his new flock. The Mass fell on August 6 — the anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. In a thick Italian accent, the staunch pacifist decried the horrors of war. One by one parishioners slipped out of the pews. By the day’s end the bishop had heard an earful. Church regulars wanted to know: Who was this bearded malihini (newcomer) lecturing them on politics?

Sister Anna McAnany suggested that Gigi focus on rehabilitating the Makaha land. She had plans for the Quonset huts: catechism class and a women’s support group. A garden might be nice, too. So the nonconformist priest patched holes and tilled the soil. Parched as it was, the land responded. Father Gigi soon had a plot of vegetables growing. He invited anybody who wanted to garden to join him.

As a youngster he’d cut hay and churned butter on his grandparents’ farm in Northern Italy. Resting in the shadow of the Swiss Alps, his home village of Uggiate traces its allegiance to the Catholic Church to the fourth century. Gigi joined the seminary at age eleven, inspired by a pastor’s assistant who was generous and kind—and who sped through town on a fancy motorcycle. From the moment Gigi donned a cassock, he was a thorn in the church’s side. Full of music, laughter and pranks, the young seminarian courted expulsion but was finally ordained in 1968.

Twenty-five and anxious to see the world, the new missionary-priest asked to go to the Amazon. Instead his superiors sent him to a new parish in the Philippines. In 1971 Father Gigi arrived with a suitcase and guitar to minister in one of the largest slums in Southeast Asia. Tondo, the squatters’ city on the outskirts of Manila, offered meager shelter to the poorest of the poor. Two hundred thousand souls lived without running water or electricity in an endless patchwork of plywood shanties. Malnourished children scavenged atop mountains of garbage while their parents sought work for next-to-nothing wages.

Father Gigi found that he couldn’t interest his new neighbors in Bible studies without addressing their more earthly concerns. “Our masses were three hours long,” he says, “because they were community meetings.” He helped the squatters advocate for themselves. Together they successfully petitioned the mayor for public water faucets and desperately needed mosquito control.

The chaos of Tondo merely reflected the turmoil brewing in the nation’s capital. Protesters rallied against economic inequality and government corruption. In September 1972 President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law. During Gigi’s five years in Tondo he watched friends vanish, to be imprisoned or murdered. One night police knocked on his door looking for dissidents; the priest hid them among a singing choir. Two days later the military chaplain identified Gigi to authorities. He was charged with political subversion, labeled a communist and deported with only the clothes on his back. “At that time,” he says, his hazel eyes ablaze with the memory, “I would have rather died than leave my work.”

Heartbroken, he asked for a three-year suspension from his priestly duties. He yearned to return to the Philippines, but the church wouldn’t allow it. He had taken an oath to serve all of God’s children, not just Filipinos, they said. But Gigi wouldn’t be mollified. He met Ed Gerlock, another priest who had been expelled from the Philippines, and the pair traveled to Hawai‘i hoping to continue their ministry with the large Filipino population here.

Once in the Islands the fathers found people laboring for social justice on many fronts. In Honolulu’s Chinatown the working-class community battled the city for permanent, subsidized housing. In Pearl City patients suffering from Hansen’s disease (leprosy) fought eviction from Hale Mohalu. The patients’ resilience and humor deeply impressed Father Gigi. He woke before dawn each morning to drive to Pearl City, administer medication and return to his duties in Wai‘anae.

Then there was Sister Anna McAnany. The petite 70-something Maryknoll nun helped Waialua plantation workers unionize and got arrested protesting the Vietnam War at Hickam Air Force Base. She introduced Father Gigi to Eric Enos, a Native Hawaiian artist who was laying pipes down in Wai‘anae valley, restoring water to ancient taro patches. He worked at the Wai‘anae Rap Center mentoring local youths who had been tagged as troublemakers. Gigi joined them, planting taro in the valley. They returned the favor, bringing a tractor and machetes down to his garden.

The Makaha farm began to flourish, as did the people caring for it. Local community leader Puanani Burgess christened it Hoa ‘Aina o Makaha, meaning “the Makaha land shared in friendship.” At first some Wai‘anae residents were suspicious of the farm, wary of yet another program designed to “help” them. A few church members still wanted to see a chapel built — the original intent for the Makaha lot. Ultimately the community embraced Hoa ‘Aina. It became an independent nonprofit, leasing the land from the church for a dollar a year.

Gigi left the priesthood and, in 1981, married Judy Seladis. She had been in the audience of his first Mass and watched how he slowly integrated into the community. “He’s a deep thinker,” she says. “He antagonizes people, but he has a good heart.” Three hundred people attended their potluck wedding reception on Mount Ka‘ala. “It was all the misfits,” laughs Gigi, “the leprosy patients, people from Chinatown and our friends here.”

Among the many relationships cultivated at the farm, the most enduring is with its neighbor, Makaha Elementary School. Initially Hoa ‘Aina was a place for kolohe (naughty) students to find grounding. As time passed, more youngsters found their way to the farm. In 1987 Makaha Elementary’s principal asked if Hoa ‘Aina could accommodate visits from the entire school. And so, long before school gardens were trendy, Makaha’s six hundred-plus students had their own five-acre farm.

The kids spend one full day a week at the farm, a luxury in this era of standardized testing and assessment-driven education. They enter through a side gate and first chant “E Ho Mai,” a Hawaiian oli requesting knowledge to flow from above. Then they get dirty with hands-on science: planting pole beans, tapioca and pak choi, fertilizing soil with worm castings, aerating the aquaculture tanks, dehydrating fruits in the solar dryer and mixing organic herbicide out of neem tree leaves.

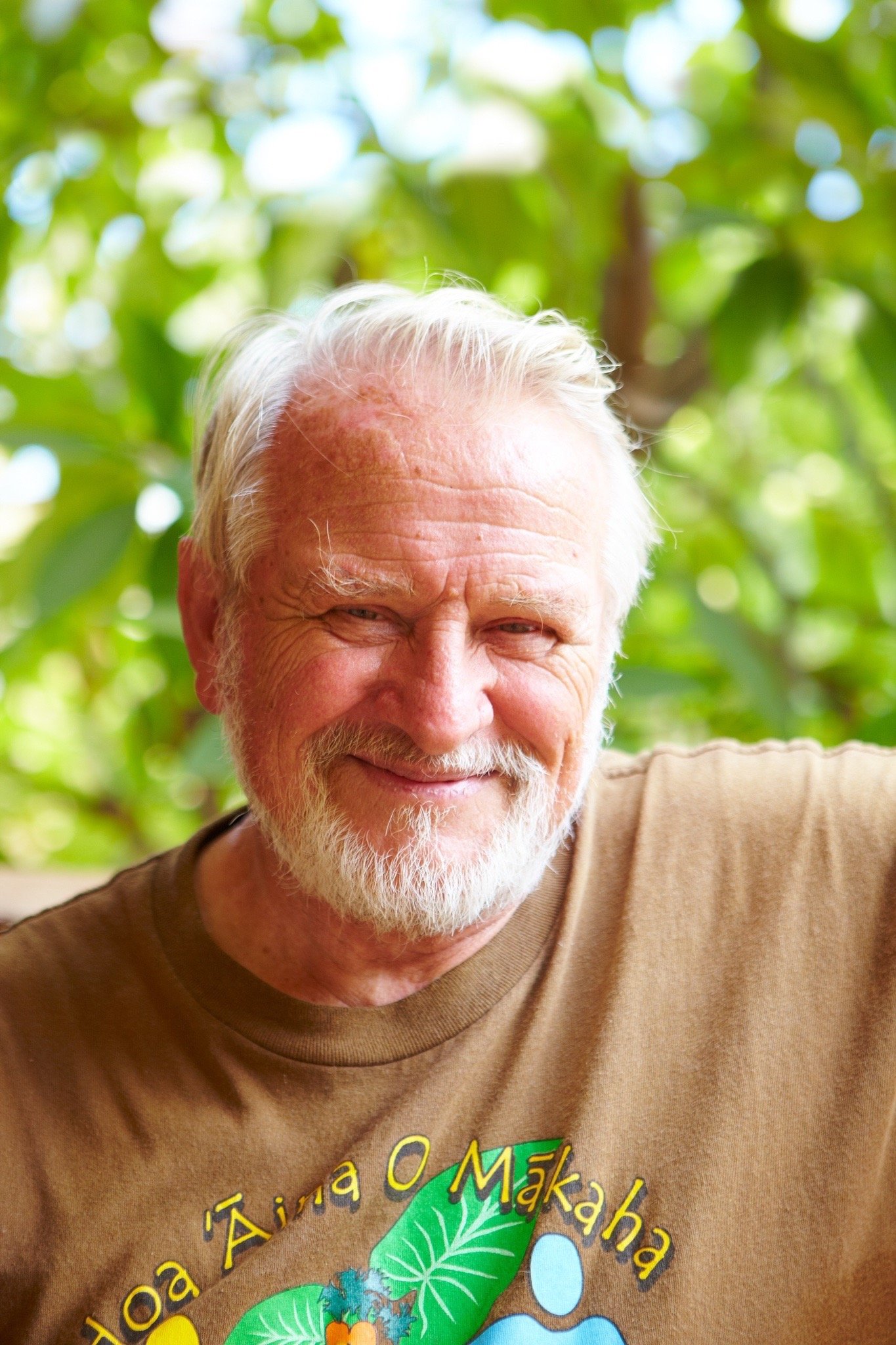

Gigi never intended to be a teacher, but it’s clearly his calling. The stout Italian bears a passing resemblance to Robin Williams and shares the comedian’s impish wit. When a fourth-grader fails to net a slippery tilapia, he praises her for catching an invisible fish — the hardest to capture, he claims. Sometimes he pretends to be his imaginary twin brother or asks for volunteers to milk the rabbits.

“Gigi cares deeply about the spirit of the child,” says Kay Fukuda, an education specialist with the University of Hawai‘i who brings students from other schools to Hoa ‘Aina. “This is a place where kids can come to experience loving a place and connecting with the ‘aina [land]. It’s a much needed balance for what’s going on in education right now.”

The farm also offers balance for what’s happening—or not happening—at home. Gigi uses garden examples to impart wisdom. A plant’s roots hold it in place, he tells his rapt audience. Transplanting can be hard on seedlings, especially if the soil is rocky and unreceptive. How do you think transplanting affects people? He encourages students to draw connections between nature and their personal lives— just as their ancestors did. Hawaiian cultural practices and values thread throughout the farm’s curriculum.

Hoa ‘Aina is a pu‘u honua, or place of refuge. When the midday sun glares relentlessly down on Makaha, the air is cool and sweet beneath the shade of the farm’s thatched hale (houses). Kids gather here to practice pounding poi — mashing steamed chunks of taro they grew a hundred feet away. Their ‘ohana (family) and teachers assemble here, too, to celebrate successes and discuss challenges facing their community. On three occasions, vandals set fire to the hale. Each time the students responded with grief, then determination to rebuild—no matter how many times necessary. When the wheelbarrow was stolen, the children, many of whom are houseless, saved pennies to replace it. They surprised Gigi with a new wheelbarrow inscribed with each of their names.

Hoa ‘Aina’s annual open house is a giant celebration. More than twelve hundred guests flood the farm. Everyone receives a plate and fork and invitation to eat their fill of sweet corn, tapioca chips and wood-fired pizza. The children nearly levitate with pride, showing off the rainbow-hued vegetables they grew and the plump fish they raised. They demonstrate how to churn butter or pluck tasseled ears of corn from the stalks. Families leave with full bellies and armfuls of fresh produce. This is the true harvest, according to Gigi. “Sustainability is not about growing more food,” he says. “It’s changing the way we relate to one another.”

Lifelong Wai‘anae resident Brenda Abaro is a prime example. The mother of five confesses she used to be more of a hands-off parent, before she learned about Hoa ‘Aina from her children. One daughter helped construct the solar house; another built the carpentry shop. When one of her girls brought home a small jar of pesto she’d made with farm-grown basil, mom cocked an eyebrow at the unfamiliar green paste. “I didn’t know what it was,” says Abaro, “but it didn’t look right.” Her daughter assured her it was delicious. A few days later Abaro visited the farm to ask for the recipe.

Now she works as Makaha Elementary’s parent facilitator and volunteer coordinator. Her office overlooks the garden. She loves hearing the children chant before entering. She’s especially excited about the farm’s newest initiative: a container garden in every Wai‘anae home. She helps host community workshops, supplying her neighbors with everything required to grow their own organic food: pots, soil, fertilizer and seedlings. Over two years Hoa ‘Aina has distributed containers gardens to more than three hundred families.

When he gave up his priestly robes Gigi became even more of a father to the Wai‘anae community. He’s made peace with the church as well. Twice he’s led cultural exchanges to Italy, and in 2000 the hula troupe associated with Hoa ‘Aina met and performed for Pope John Paul II.

Gigi, who just turned 70, lives with Judy in one of the original Quonset huts. Their son Pomaika‘i Cocquio has absorbed many of the farm’s responsibilities, but dad still wakes at 4 a.m. to answer email, feed the animals and tidy up before the blazing sun crests Mount Ka‘ala. Occasionally Gigi seeks solace in a tiny room decorated with a life-size triptych of St. Francis of Assisi, St. Damien and Mother Marianne of Moloka‘i. He talks to God but doesn’t recite the formal prayers of his past. His views on that communication have changed: Now, he says, “Gardening is praying.”