The Farm Where They Grow People

June 02, 2010 | Original post at Midweek

By Sarah Pacheco

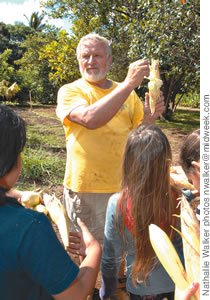

Gigi Cocquio shares his knowledge of corn harvesting with students from Kapolei Elementary School.

Gigi, Gigi, Father Gigi, What does your garden grow?

Nestled in the heart of Makaha on five acres of once-barren land grows a garden of fruits, vegetables, plants and animals. But Hoa ʻĀina O Mākaha, or “The Farm” as it is affectionately known by community residents, is also an eden for children to plant roots in friendship, stewardship and aloha.

“We grow people,” says executive director Luigi “Gigi” Cocquio. “If we learn virtually how to grow ourselves – understand who we are – the rest comes. But the main thing is to offer the possibility.”

Born in the small village of Uggiate, Italy, Cocquio settled in Mākaha 31 years ago shortly after being deported from the Philippines in 1976. The Catholic priest had been in the country since 1971 struggling for social justice in Tondo, the largest slum shantytown in Southeast Asia where more than 200,000 people lived in poverty.

A year into his five-year mission, former president Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, stripping away the freedom to organize or to engage in free speech. Cocquio and his fellow priests provided their church as a gathering place where people could safely reflect on politics and oppression. But soon Marcos and his regime came knocking.

Ceny San Pedro explains where bananas come from.

“People were killed and tortured and would disappear, and I couldn’t keep my mouth shut,” Cocquio remembers. “I wasn’t organizing, I was just staying with the people. And that didn’t go too well with the president, and also with the church. Eventually, they picked me up from the house, brought me to the airport, straight on a plane back to Italy, like this – T-shirt, pants and sandals, that’s all I had.

Ceny San Pedro explains where bananas come from

“And I had one peso in my pocket,” he adds. “I had two pesos, but when they arrested me this poor lady came to me and asked for money to buy milk for her family, so I gave her one peso. And that was really very painful for many years. I wished they killed me instead of kicking me out because the work was so beautiful, the people so incredible, I felt so at home.”

His passion for human rights continued in Hawaii. Soon after his arrival he became involved with advocating for leprosy patients of Hale Mohalu in Pearl City and with the Church of the Sacred Heart in Waianae Valley. It was at the parish where he met Sister Anna McAnany of Maryknoll, who took the young priest out to a piece of deserted land in Makaha leased by the Roman Catholic Church Diocese of Honolulu and offered up a simple challenge.

Kacey Walker, 7, is surprised by the pecking of a goose

“This nun said, ‘We have to do something,’” says Cocquio. “And you cannot say no to an older nun, so I said sure, let’s do something.”

Soon after their conversation Cocquio moved into one of three Quonsets on the property, barracks left over from World War II. He was joined by Brother Ed Gerlock and Eric Enos of Ka’ala Farm, who came with a group of at-risk youth from the Waianae Rap Center to help transform the land from wild brush into a place of peace.

Kacey Walker, 7, is surprised by the pecking of a goose

“There were no plans. The ‘plan’ was, let’s clear a piece of land and see what happens,” Cocquio says. “I didn’t know about irrigation, I didn’t know about farming, I didn’t know about building, I didn’t know about cooking. Honest. So I had to learn everything, and that’s what we did – just put down the first pipe and start planting.”

As The Farm was steadily growing, teachers from neighboring Mākaha Elementary School also began to show interest in the lot. Cocquio allowed them a small vegetable patch to maintain with their students. One day, principal Hazel Sumile approached Cocquio with a proposition.

“She said, ‘Why don’t you work with all the kids?’ And I said sure. That’s what I told the nun, and that’s what I told her. I always said sure,” Cocquio says in his even, patient tone. “I never knew what I was getting into, but that’s how it goes.”

Today the keiki of Mākaha Elementary cross the threshold to Hoa ‘Āina every day, but not before respectively stopping to chant for permission to enter. They visit to tend to their gardens; take care of the goats, rabbits, ducks and chickens that live there; learn Hawaiiana, hula and about the ancient ahupua’a system; conduct science experiments and learn about alternative energy; and, most importantly, they visit to gain knowledge within themselves.

“In education, the word itself means ‘to lead out’ from Latin, the little Latin I remember,” Cocquio says. “It means that the thing is already inside the person, and we have to help; we’re helping each other take it out so we can understand.”

From there Na Keiki O Ka ‘Āina was born. Each year more than 6,000 students, teachers and parents from schools both private and public come to The Farm to toil in the soil. Cocquio reveals that this year alone 23 schools had to be put on a waiting list because of time constraints.

The field trip is such an anticipated journey that when schools have to cancel because of rainy weather, children throw tantrums, so heartbroken and even offended that they do not get to see Mr. Gigi and his farm. In fact, The Farm also has been known to ruin trips to other botanical gardens on the island. Even the zoo pales in comparison.

“Many of the schools come from town, and this is the first time sometimes that they see these kinds of things,” says Cocquio, whose family – son Pomaikai, stepsons Buddy and Scott, and wife Judy – all at one point lived and worked on The Farm.

“Here they plant, they harvest, they touch, they feel, they taste the fruits and play with the animals,” he adds. “To me that’s a very powerful experience.”

Under the guidance of Bishop Joseph Ferrario and the Hoa ‘Āina board of directors, Hoa ʻĀina O Mākaha became a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization in 1992 to ensure that keiki and visitors from all over the world could experience this connection for years to come.

“It doesn’t matter how much we plant, how much we harvest, but it’s how much we together with the children can be able to relate to each other, to relate to the land and have feelings for this experience,” Cocquio says.

“Anything that comes from an experience comes from the heart. If it comes from the mind, really if it involves a lot of thinking, sometimes it is not easy to figure out, especially for our children. But if it comes from the heart, easy to recognize.”